Custom Computer Keyboard

I built a custom keyboard for a woman with cerebral palsy.

This project started at ITP camp in 2016 in a class taught by ITP alumni Claire Kearney-Volpe and Ben Light. The goal of the class was to build custom keyboards for disabled people who have difficulty using traditional keyboards.

In the class we met with several members of Adapt Community Network and discussed their experiences using computer keyboards. Traditional keyboards often do not meet the needs of disabled people. We talked about ways we could re-design a keyboard to make computers more accessible and meet their usability needs.

I worked with a woman named Shaniqua. She didn't like the traditional key arrangement of a QWERTY keyboard and often found it difficult to find the next key she needed to type. There were some keys she didn't use at all and she thought the keys were too close together.

I designed a keyboard layout in Inkscape and used ITP's 60 Watt laser cutter to cut and etch all of the parts. There are 73 keys on this keyboard so the cutting took almost 4 hours to complete.

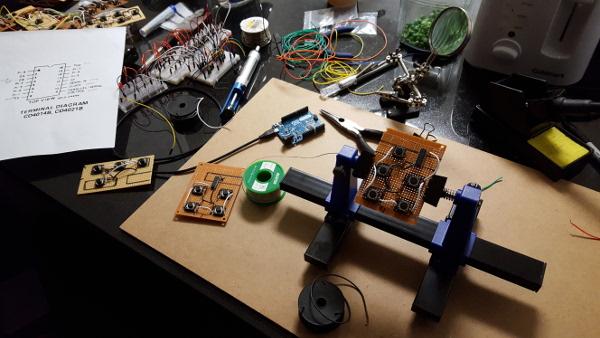

Next I needed to understand the electronics that go inside the keyboard. I had not used a shift register before so I did some experimenting to understand how this is supposed to work:

Finally, the actual assembly. This part was very difficult and it took me a long time to figure out something that made sense and seemed achievable. There are so many buttons...how am I supposed to organize the buttons, the wires, the shift registers, and the resistors?

I started by soldering the buttons into place in their correct locations on each circuit-board along with resistors and wires for power and ground. Each circuit-board connected the power and ground wires to each other so I only had to add two wires from one board to the next to power the buttons.

Then I divided up the circuit-boards into "key regions." Each region is controlled by shift registers in that region. The circuit-boards in each region share power and ground with each other.

I completed the soldering for each key region and tested them with an Arduino to verify that the buttons worked. Then I linked the regions together, connecting the shift registers' data, latch, and clock wires and adding power and ground. Everything was attached to the acrylic using velcro to keep the circuit-boards in the proper place.

Clearly that's a messy collection of wires, and the solder joints on the other side aren't any better. There's about 50 ft of wire on both sides of the circuit-boards and hundreds of solder joints. Nevertheless, the buttons work like they're supposed to. I added some scotch tape to keep the wires under control and assembled the keyboard buttons.

The keys are multi-colored using a collection of Sharpie markers I bought for this purpose. When I met with Shaniqua we came up with the idea of using colors to make the keys easier to find. The numbers and vowels are Shaniqua's favorite color, pink.

Below is the final keyboard. The keyboard is resting on a specially made stand designed to prop up the keyboard on a small incline. Shaniqua didn't want the keyboard to be flat on the table.

I wrote documentation explaining how to configure the action keys at the top of the keyboard and other information to help someone repair the keyboard if need-be. The Arduino code is also available online.

Here are my blog posts for this project:

- Thursday, June 30, 2016 10:12 PM Making a custom keyboard at ITP Camp (Part 1)

- Sunday, August 7, 2016 10:12 PM Making a custom keyboard at home (Part 2)

- Thursday, December 1, 2016 1:59 AM Finishing a custom keyboard at home (Part 3)

- Tuesday, March 7, 2017 12:23 PM Mostly complete keyboard (Part 4)

- Friday, September 15, 2017 2:42 PM Complete custom keyboard (Part 5)

There are some things about this project that didn't go so well. The arrangement of the buttons and wires was hard to manage and caused many problems and mistakes. I did it that way because the only way I understood how to build this with the resources I had available to me was to have all of the components together on a single plane of circuit-boards. On the other hand, I learned a lot about good and bad solder joints and I got a lot of practice diagnosing problems with a multimeter and de-soldering. The electronics work but they caused a lot of late nights and stress. In the future I will be much more disciplined about how I solder connections in circuits.

The keyboard was built as a prototype, and one that Shaniqua can experiment with and provide feedback on to help build future keyboards for herself and other members of United Cerebral Palsy. This keyboard isn't perfect but it is something that she can use at her job doing office work. I am very happy to have built this. I am also looking forward to the opportunity to build more tools like this for disabled people as an ITP student; I learned a lot from this process and know I can do even better next time.