Color Blindness Simulation Research

To understand color blindness simulation, one must first understand how human vision works. Our eyes enable us to see, but how?

Human Visual System

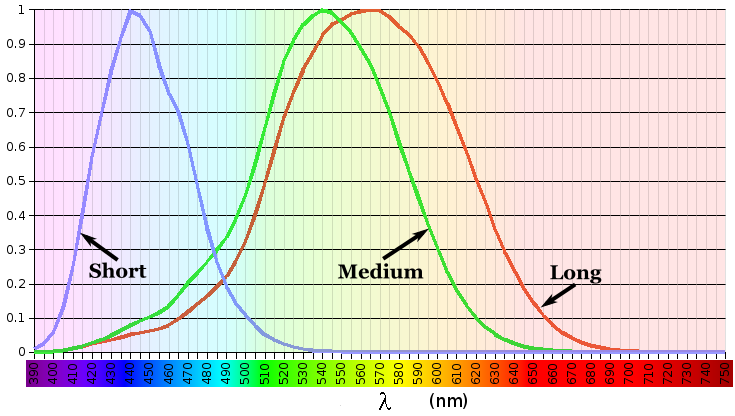

A human trichromat's eyes contain 3 types of cone cells, each of which has a unique sensitivity to different wavelengths of light. These "spectral sensitivities" mean the cone cells are "stimulated" by different wavelengths of light. Our visual system experiences color by comparing the relative stimuli of different cone cells.

The above chart plots the normalized stimulation levels of the cones when they are exposed to different wavelengths of light. Sometimes the cones are called blue, green, and red cones, corresponding to wavelengths near the "peaks" of each line. This is somewhat misleading as each of the cones respond to a wide range of wavelengths. It also doesn't correspond to the red, green, and blue terms used for defining colors in Processing. A better terminology is to use short, medium, and long, or S, M, and L, as I will do on this page.

LMS Color Space

To simulate color blindness, we need to think about colors in terms of stimulations to the L, M, and S cones in the human eye. To help us do that, we will convert our colors from the sRGB color space we use in Processing to a new color space called LMS.

The first step in this process is to remove the gamma correction applied to Processing's colors. The red, green, and blue values are represented internally as integers in the range \([0, 255]\). In this color representation a value of 200 appears to humans as twice as intense as a value of 100, but this does not correspond to a doubling of the light's energy in the physical world. Gamma correction transforms color intensities in the physical world into an arrangement that appears more uniform to humans. Gamma correction is important but we need to remove it to do math on numerical color values.

For each of a Processing color's red, green and blue values, we will transform the color into what is called Linear RGB space by removing the gamma correction with this formula:

Gamma correction can later be re-applied with the inverse formula:

After removing gamma correction, each of the resulting Linear RGB values are floats in the range \([0, 1]\). We can apply this formula to the red, green, and blue values of an arbitrary Processing color \(c\) and put the result in a vector, like so:

This color in the Linear RGB color space can be converted to the XYZ color space using a transformation matrix \(M_{sRGB}\) obtained from www.brucelindbloom.com. This sRGB matrix is calculated from the XYZ values of the 3 primaries used in this color space.

This can then be converted from the XYZ color space to the LMS color space using the Hunt-Pointer-Estevez transformation matrix \(M_{HPE}\):

For simplicity we can multiply \(M_{sRGB}\) and \(M_{LMS}\) to calculate one transformation matrix \(T\) for converting colors from the Linear RGB color space to the LMS color space.

To convert colors from the LMS color space back to Linear RGB, we simply multiply by the inverse \(T^{-1}\).

Color Blindness Simulation

Now that we can convert our Processing colors to the LMS color space, we can begin to think about color blindness simulation. Let's start by simulating Protanopia. Protanopes are missing L cones. We will attempt to simulate this by setting \(l_{c}=0\), like so:

This seems like a reasonable way to simulate missing L cones, right? This change can be represented mathematically with a (transformation) simulation matrix \(S\) that we multiply our LMS color vector by:

This modified color in LMS color space can then be converted back to Linear RGB using \(T^{-1}\) and gamma correction re-applied.

Therefore the color blindness simulation process is simply some matrix multiplications to transform a Processing color \(c\) to the simulated color \(c'\), with gamma calculations at the beginning and end.

We can do this for every pixel in the Processing sketch. After re-applying gamma correction, we should be simulating Protanopia.

Let's test this to see how it works:

The right picture seems darker and white and grays are now a greenish blue color. Since we know that Protanopes can correctly distinguish greens and blues from grays and white, it doesn't make sense that color blindness simulation would alter these colors like that. This simulation is flawed.

The problem is with the simulation matrix \(S\). Let's consider a different matrix \(S_{p}\) with variables \(q_1\) and \(q_2\) for two of the matrix elements:

Instead of setting \(l_{c}=0\), we will make it a function of \(m_{c}\) and \(s_{c}\). We will solve for \(q_1\) and \(q_2\) under the constraint that the colors white and blue need to stay the same. Referring to the spectral sensitivity chart at the top of this page, it seems reasonable to make the assumption that a Protanope's missing L cones will not affect their ability to see the color blue.

The choice to use blue is not arbitrary. It makes sense that we need to choose a color that is far away from the peak of the L cone response curve on the spectral sensitivity chart, but why not purple, which is to the left of blue?

To answer this question, you must first understand what color is being represented at that end of the chart. Recall that purple is not a spectral color, but violet is. So the color being represented there is actually violet. But violet is outside the color gamut of the standard RGB color space, and therefore cannot be accurately portrayed by your computer screen or encoded into the image you see on this page. The best approximation for the color to put there is purple, and if you analyze those pixels in your favorite image editor, you will see that those pixels are in fact purple. This might seem a bit confusing at first, but it will make more sense once you understand that no computer monitor or color printer can represent the full range of colors visible to humans. It also means that images like this one are a little bit hand-wavy in that none of the colors outside the sRGB triangle are actually represented correctly.

Purple is a combination of red and blue, and since it contains red, it can't be used here. Violet would be a good choice but we can't actually specify it in sRGB space, so it can't be used. Since we can only use colors that can be represented in the standard RGB color space, the blue primary color is the best choice.

The blue primary values in Linear RGB space are \(r_{b}=g_{b}=0\) and \(b_{b}=1\). This must be converted to the LMS color space:

The justification for the assumption about the color white is different because white covers the entire spectrum and in a trichromat that involves stimulation to the L cones. The color white provides maximum stimulation to the S, M, and L cones. One could argue that a Protanope might confuse it with another color that also provides maximum stimulation to the S and M cones but less stimulation to the L cone.

This argument would be correct, if such a color were to exist. Have another look at the spectral sensitivity chart at the top of this page. Because of the overlap between the M and L response curves, it is impossible to stimulate the M cone without also providing stimulation to the L cone. Any color that provides maximum stimulation to the M cone must also provide close to the maximum stimulation to the L cone.

Of course one can imagine LMS color values where this is not the case, but when that hypothetical LMS color is converted back to Linear RGB space with the inverse transformation matrix \(T^{-1}\), the result will be a color with values outside the required range \([0, 1]\). I would call this an infeasible color. That color may actually exist and be visible to humans but it will be outside the standard RGB color gamut. It may also be outside the color region that is visible to humans, in the scary world of imaginary colors. In any case, this isn't a color you will see on your computer screen.

You can experiment with this by doing the math yourself or by using the LMS Color Model example code provided with the ColorBlindness library.

Since maximum stimulation to the S and M cones is unique to the color white, the assumption must be valid.

In Linear RGB space, the color white is a vector of ones. This must also be converted to the LMS color space:

Applying the simulation matrix \(S_{p}\) yields:

similarly, for white:

We need to find the \(q_1\) and \(q_2\) values so that these equations hold true:

If this is true, the simulation matrix won't change the \(l\), \(m\), or \(s\) values for white or the blue primary color. When those LMS colors are converted back to Linear RGB space with \(T^{-1}\), they will be the same as when they started. We should get a better result in our simulation because the color blindness simulation won't alter white or blue.

We can do some math and solve for \(q_1\) and \(q_2\):

Using the matrix \(T\) we can calculate the \(l\), \(m\), and \(s\) values for white and blue and then calculate \(q_1\) and \(q_2\).

For white, it's simply:

And for the blue primary, it's:

Now we can calculate \(q_1\) and \(q_2\) to complete our Protanopia simulation matrix:

When we test this new matrix we get a much better result:

Simulating Deuteranopia can be done using a similar approach. Deuteranopes are missing the M cones, so the simulation matrix has this form:

Repeating the above procedure with the same assumptions will result in this simulation matrix:

Tritanopes are missing the S cones. We could again repeat the above procedure, but we would be making a mistake. Look at the spectral sensitivity chart at the top of this page and consider the assumption about the color blue. It is not correct to make the assumption that a Tritanope's missing S cones will not affect their ability to see the color blue. Instead, we will make a similar assumption about the color red. That assumption gives us this simulation matrix:

Errors in Open Source Software

Interestingly, I found many color blindness tools that incorrectly simulate Tritanopia because their calculations make the erroneous assumption about the color blue. You can find examples of this if you search around online. I was able to exactly duplicate the Tritanopia simulation matrix used in other people's code when I used the same RGB to LMS color space transformation matrix that they use and make the incorrect assumption about the color blue.

Since color blindness simulations are hard to understand or verify, I suspect that programmers are copying algorithms from elsewhere without understanding exactly how they work or where the numbers come from. I am writing this documentation here as an attempt to correct that.

A widely cited paper in this area is Digital Video Colourmaps for Checking the Legibility of Displays by Dichromats by Vienot, Brettel, and Mollon. I studied this paper closely to understand the math behind color blindness simulations. You will notice that the paper calculates the simulation matrices for Protanopia and Deuteranopia only. A reader might have used the results of step 4 to make a Tritanopia simulation matrix without fully understanding the assumptions that went into those calculations.

That paper solves the equations using a slightly different approach. They make the assumption that white, blue, and black are all unchanged by the simulation. These three colors define a single plane through the 3-dimensional LMS color space. They calculate the parameters for that plane by taking the cross product of 2 vectors pointing from black to both white and blue. They are doing the same thing that I am doing here, which is reducing a 3 dimensional space down to 2 dimensions under the constraint that the plane must pass through a few specific colors (points) in the LMS color space. It arrives at the same result but is maybe less intuitive. It should be clear that a colorblind person's color vision must be represented as a 2 dimensional surface because they only have 2 functioning cones. Our calculations above were essentially about finding the proper orientation of that plane in the 3 dimensional LMS color space. Color blindness simulation is then a process of mapping colors in the 3 dimensional space onto that plane.

The paper also uses a XYZ to LMS transformation matrix from a seminal paper by color scientists Smith and Pokorny. These transformation matrices must be measured empirically. I used the more current Hunt-Pointer-Estevez transformation matrix \(M_{HPE}\).

Many color blindness daltonization tools also use an incorrect matrix for color correction. Regrettably this statement includes previous versions of this Colorblindness library. The main idea behind daltonization is to measure the error between the original color and the simulated color and then apply a correction to "rotate" the colors in a way that makes them more distinguishable to colorblind users. As one would (should) expect, there is a different rotation matrix for each of the three types of color blindness. However, most daltonization algorithms use only the protanopia error correction matrix. This is a mistake. Thanks to Nicholas Frangie at Demiurge Studios for questioning this part of the library.

The error correction matrix for protanopia is not the same as the error correction matrix for deuteranopia or tritanopia. For deuteranopia the rotation matrix is:

And for tritanopia the rotation matrix is:

This library now uses correct error correction matrices for each type of color blindness for daltonization. See Evaluating color vision deficiency daltonization methods using a behavioral visual-search method by Simon-Liedtke and Farup for more information about this.

Achromatopsia (Monochromatism)

We will complete our color blindness discussion by simulating the color deficiencies of Achromatopsia, or Monochromacy. There are two kinds of Monochromacy: Rod Monochromacy, and Cone Monochromacy.

Blue-Cone Monochromats

Cone Monochromats are missing both the M and L cones and are often called Blue-Cone Monochromats. The form of their simulation matrix is:

Following a similar approach as above using only an assumption about the color white, we get:

If we multiply the simulation and transformation matrices together, we see we can simplify this process:

Since the simulated colors are always grayscale values, we can simplify our process by creating a simulation vector and taking a dot product with the Linear RGB color:

The blue-cone monochromat simulated color is then:

Achromatopsia

The ColorBlindness library uses this simulation vector for achromatopsia or rod monochromats:

These are the scotopic coefficients for simulating night vision, or vision with only rod cells. These numbers come from the research paper Calculation of Mesopic Luminance Using per Pixel S/P Ratios Measured with Digital Imaging by Maksimainen, Kurkela, Bhusal, and Hyyppä.

Previous versions of this library incorrectly simulated achromatopsia with the below coefficients. These coefficients are for photopic vision, and are often used for measuring the luminance of RGB colors.

Note that the previously mentioned paper mistyped the red coefficient as 0.2162. The photopic coefficients in the paper do not sum to 1.0.

A Rod Monochromat essentially has only their night vision available to them to see. They will be most comfortable at nighttime or at dusk as their eyes will be overwhelmed in the daytime. They may wear dark glasses during the day to compensate. A Blue Cone Monochromat can function like a dichromat in low light conditions when their blue cones and rods are both active. I have seen blue cone monochromat color simulations on the web that simulate the color deficiency in this way but I think it is less helpful because that situation does not match a user looking at a brightly-lit computer monitor.

Experimentation in Processing

In any case, this library is fully customizable and you are free to adjust the transformation matrices and simulation matrices and vectors as you see fit. Refer to the CustomParameters sketch in the ColorBlindness Tutorial example code. For your convenience, there is also a built-in custom deficiency setting to facilitate experimentation. Below is an example of how to use it to simulate green-cone monochromacy. You can set it to whatever you want without altering the other matrices.