Dubois Optimization

The Dubois Anaglyphs are implemented in Camera3D using highly optimized code, resulting in a performance improvement of about 300x over the naive implementation.

The algorithm has three steps, outlined here. It converts colors from standard RGB to linear RGB, does some linear algebra in linear RGB space, and then converts the results back to standard RGB. The two color space conversions require exponentials and are way too slow for a realtime animation to do multiple times for every pixel of every frame.

My implementation reduces all of that math to one addition and a handful of bitwise operations and array lookups into pre-computed tables.

To understand how I did this, consider how Processing manages colors. The color type is really just a 32 bit integer, with 8 bits for each of the colors red, green and blue. The remaining 8 bits is the alpha value, for transparency.

Eight bits means the possible values are the integers from 0 to 255. I can easily pre-compute the sRGB gamma function for all 256 possible values.

Since none of the colors will be transparent, I know that there are \(256^3 = 16777216\) possible colors in Processing. Therefore, for any sRGB color \(\left \{ R', G', B' \right \}\) I can pre-compute its linear RGB equivalent \(\left \{ R, G, B \right \}\).

I can then take the next step and pre-compute the multiplication of every possible linear RGB color \(\left \{ R, G, B \right \}\) by the left and right conversion matrices for the desired anaglyph type:

In an anaglyph, there is one color for the left image and one color for the right image. Both have to be converted to linear RGB, multiplied by their respective conversion matrix, and then added together. I can't pre-compute that addition for every possible left and right color combination because there are 281 trillion permutations. This is the one addition in my implementation.

After computing the addition and clipping the result to \([0, 1]\), the linear RGB anaglyph color needs to be converted back to sRGB. This conversion can also be pre-computed.

But how many values should this be pre-computed for? Not 256. The gamma correction function is nonlinear, and the output of the matrix calculations will not line up with 256 discrete values. Since the results will not be uniform in the range \([0, 1]\), there will actually be a loss of color accuracy for values close to zero if I were to try to do that.

What the code actually does is pre-compute the gamma correction for \(2^{20}=1048576\) values in the range \([0, 1]\). But why that many?

A few more details about the implementation will explain.

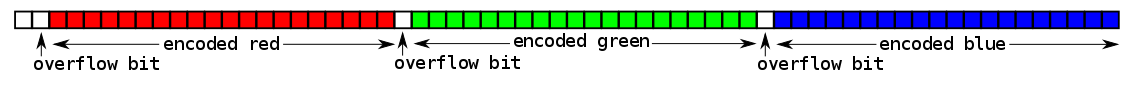

The output of the matrix multiplication is a vector of three floats, each clipped the range \([0, 1]\). Map each float to a 20 bit integer in the range \([0, 2^{20}-1]\), and arrange the bits into a 64 bit integer, like so:

This is how the algorithm encodes the three floats into one 64 bit integer.

If I have one 64 bit integer for the left matrix and one 64 bit integer for the right matrix, adding the two 64 bit integers together will add three pairs of encoded floats with one addition operation. Each of the 20 bit integers may overflow to a 21st bit, but that's OK, since there was a 1 bit gap between each of the integers. If any of those overflow bits are equal to 1 after the addition, that means the float would have been clipped to a value of 1 and the Processing color value would become 255. If the overflow bit is not equal to 1, I can use the resulting 20 bit integer to look up the correct Processing color value in the pre-computed 20 bit gamma correction lookup table.

That's how the algorithm works. Besides the above, there are just some bitshifting and bitmasks to encode the 20 bit integers into a 64 bit integer value and then to decode the outcome of the addition of two 64 bit integer values. Have a look at the code on github to see for yourself.

The pre-computed lookup tables requires one 64 bit integer for all possible \(256^3\) Processing colors, and there is one lookup table for each of the left and right matrices. This will use 256 MB of RAM. The gamma correction lookup table uses an additional 4 MB of RAM. For most computers, this won't be an issue.

Camera3D also comes with smaller memory footprint implementation that uses 128 MB of RAM for its lookup tables but will result in a loss of color accuracy for desaturated colors. It also comes with a naive implementation that does not do any of the above optimizations so you can see the performance improvement. To experiment with either, adapt the below code to your sketch.

import camera3D.*; import camera3D.generators.*; void setup() { size(500, 500, P3D); camera3D = new Camera3D(this); StereoscopicGenerator stereoGenerator = DuboisAnaglyphGeneratorNaive.createRedCyanGenerator(); // (or DuboisAnaglyphGenerator32bitLUT.createRedCyanGenerator()) stereoGenerator.setDivergence(1.5); camera3D.setGenerator(stereoGenerator); }