Towel Rack

For my midterm project I created this towel rack for my apartment:

This is a double towel rack with 1 1/8" diameter bars for the towels. I specifically wanted thicker bars because I thought it would help keep the two sides of the towel from touching each other, facilitating drying. It also happens that the only place in my bathroom where I could possibly put a towel rack is in a location between the shower and the door that is a little bit less than 25" wide. Most towel racks I could buy at the store with 24" bars are too wide to fit in that space. Towel racks with 18" bars are too small for my towels. My current towel rack is a cheap wooden towel rack with a 24" bar that I bought at the store that I trimmed to be slightly shorter using the sander in the shop. I'm excited to soon replace it with this one.

Design

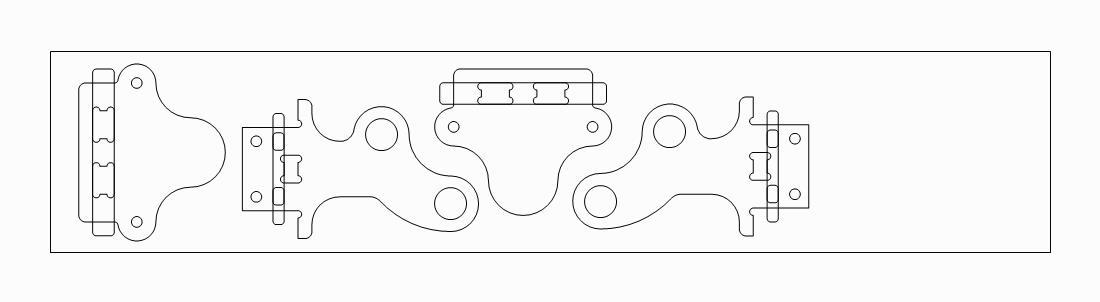

Building on my previous CNC experiments with joints and holes I designed the below towel rack using Vectorworks. Observe the large rectangle; it is the size of the piece of wood I bought at the hardware store. The pieces to be cut are inside. That rectangle helped me layout the pieces on the wood in a compact way with some wood left over. That decision was helpful later.

You'll also notice I added two sacrificial appendages for the two pieces that won't be screwed into the wall. As I learned on previous jobs, all of these CNC'ed parts will move when the final cut is complete, potentially ruining the piece. To counter this I wanted to screw down the pieces to the spoiler board. The two pieces that will eventually be mounted to the wall have screw holes built into their design. The other two pieces do not. The appendages will be screwed down and have their link to the main piece mostly cut during the last pass of the router. My plan was to remove the piece and cut off the appendage using the circular saw in the shop, and maybe sand a bit if needed. The appendage is attached to the piece I wanted along the fingers of the finger tenon joint and therefore would be inside the other piece in the final work. Therefore nobody would see it and it didn't have to have a perfect edge.

CNC

After creating the design I setup the toolpaths on the CAM machine and prepared the CNC.

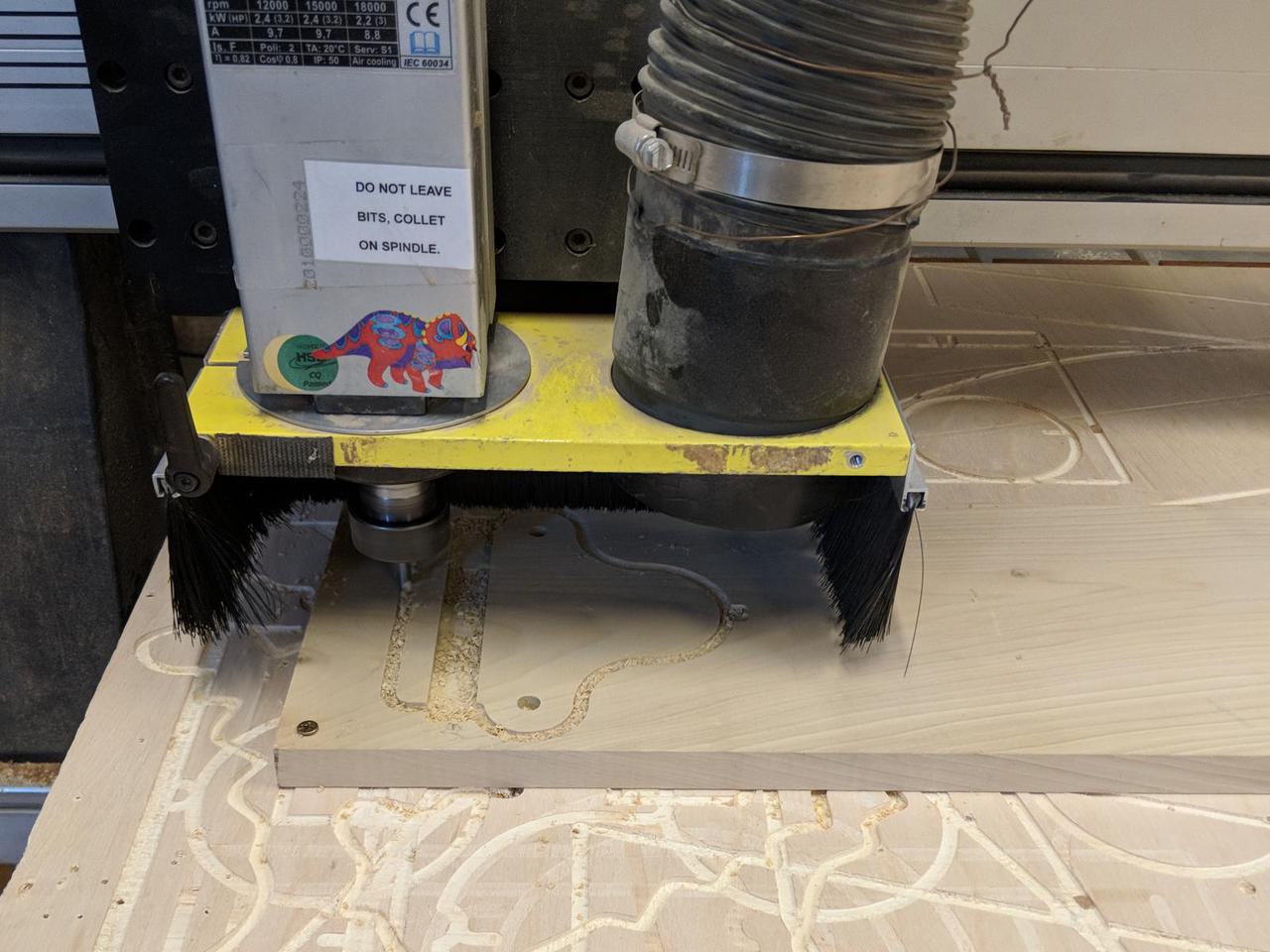

The job started out well.

My plan with the screwed down appendages worked as expected.

When the CNC finished with this piece it made the final cut on the far side of the piece where the lead in/out point is. As soon as the CNC made that cut the piece popped up a little bit off the spoiler board. Perhaps I screwed down the appendage too tightly or my wood wasn't complete flat. That movement put a small dent in that part of the piece. Nothing a little sandpaper can't fix.

The last step for this piece is for the CNC to remove most of the material connecting the appendage from my part.

This is the final result. The appendage was easily removed and the joint fingers were sanded a bit.

Happily the two pieces fit together perfectly with no wiggle in any direction. This is exactly as I expected. You can see the small dent at the end.

Feeling encouraged, I started the CNC'ing for the other half of the towel rack. And that's where the trouble began.

I needed to repeatedly pause the CNC job to screw down the pieces, and to screw down the pieces I needed to manually move the CNC router away from the wood to give me room to get in there with an electric screwdriver. While moving the CNC router to screw down the third piece, I mistakenly jogged the machine along the Y axis instead of the Z axis. This plowed my bit directly through my wood, breaking off a piece of the wood. Luckily it was near the edge of the wood and my bit was stronger than that part of the wood. This could have easily been a broken bit.

You can see the damaged wood below.

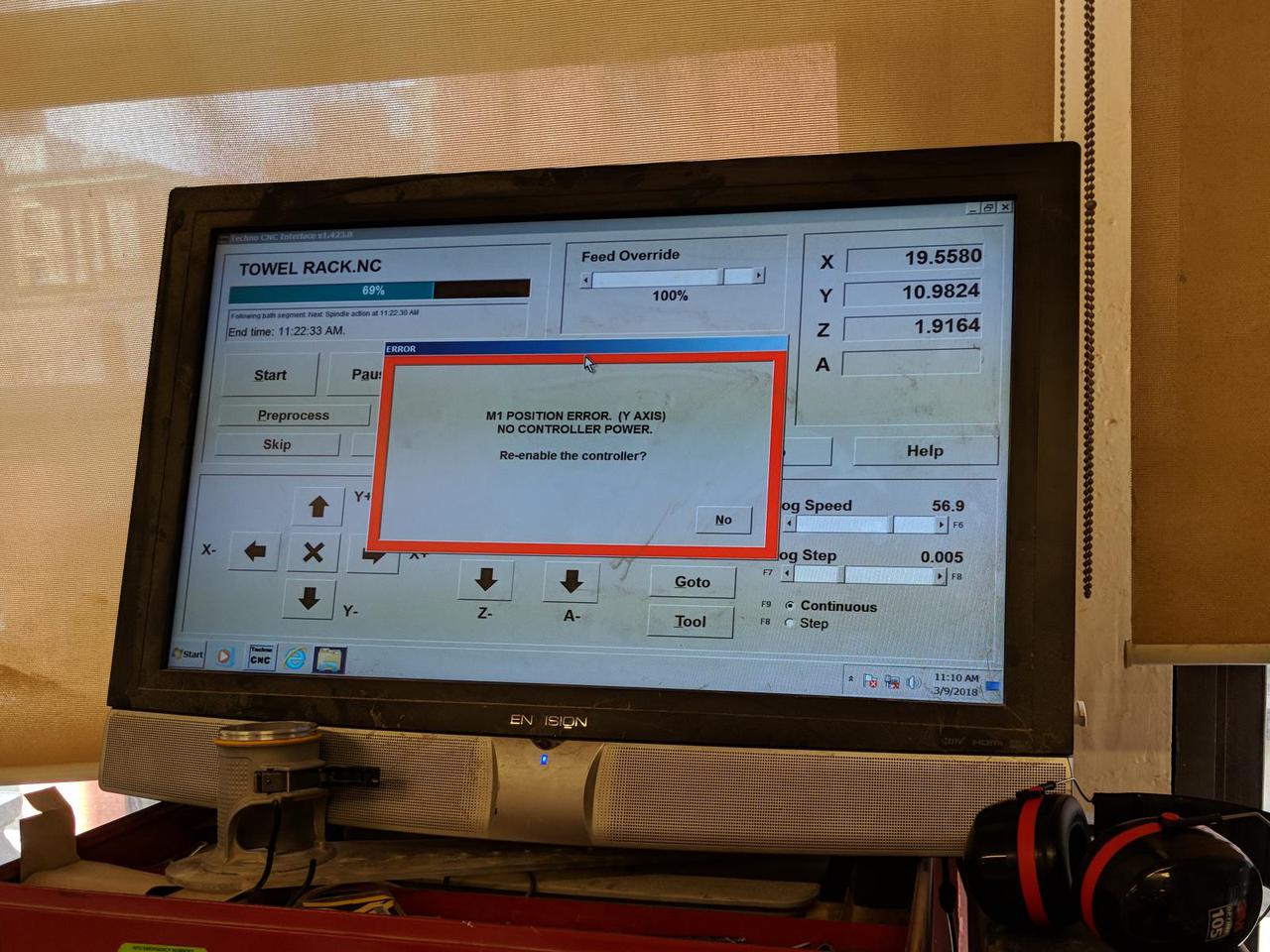

To make matters worse, the CNC refused to continue the job. I got this error:

I don't know what I would have done if John hadn't been in the shop. Somehow the CNC's positioning got thrown off because of my mistake. He told me I had to turn off the CNC while he manually moved the CNC router to reset the machine. Since the CNC was being reset, I knew I was going to have to re-zero the CNC to continue the job. I didn't think I could re-zero it accurately enough for me to properly continue the half-completed piece so I went back to Vectorworks to put a new piece on the unused part of the wood. I made a new job on the CAM and went back to the CNC to continue the project.

I again paused the job to screw down the piece, this time being very careful to not mix up the Y and Z axes. I didn't have any wood left and couldn't afford another problem.

Unfortunately fate was not on my side. I immediately got the same error message after adding the screws. John had to again reset the CNC.

Since I had no extra wood left I was going to have to re-zero the machine and continue the same part. It was in the middle of the exterior contour cut. If I didn't re-zero the machine with a high degree of accuracy the part was going to be worthless, but I was going to at least try.

Happily I successfully re-zeroed the machine with high precision. It was slightly noticeable but only a tiny fraction of an inch off. With a little bit of sandpaper nobody would ever notice.

Since my re-zeroing attempt worked I might have also been able to recover the abandoned piece after the first reset. Also, if my successful re-zeroing attempt wasn't good enough I could have tried re-zeroing again and continuing the abandoned piece. In any case I was determined to finish the CNC'ing and wasn't going to give up without a fight.

The final piece was CNC'ed without incident.

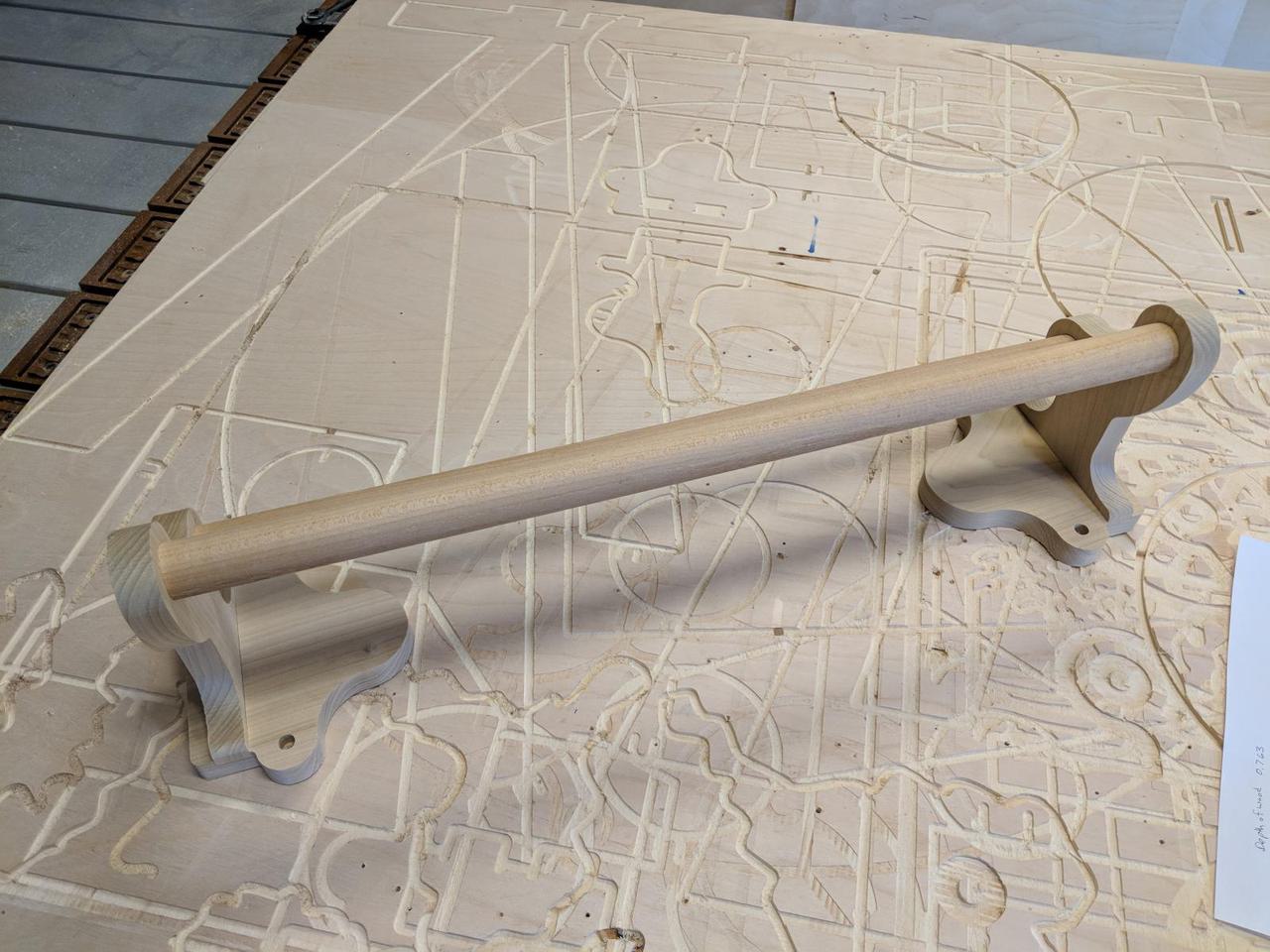

Much to my delight, all the pieces fit together properly. It looks great!

Later John complimented me on my ability to keep my cool despite the problems with the CNC. I didn't invent any new 4-letter words or anything. I also learned a lot from the experience. There are some things I would do differently to better help myself recover from a CNC reset. In particular I would consider the order of my toolpath operations and how well I could recover from a reset.

Finishing

The CNC'ing work was complete but I had more to do. First I had to glue together the parts. I used 2 cents of the $4 wood glue I bought for this project:

I then applied two coats of a stain-polyurethane mix I found at the hardware store.

It should be noted that I am using three different kinds of wood. The bars are made of hardwood and the end pieces are made of poplar. The screw caps are made of birch. The stain did not affect the three kinds of wood in the same way. The hardwood has a bit of a red hue and the poplar has a slight green hue. I applied two coats to try to get it to converge somewhat with limited success. Since the birch and hardwood look the same with the stain, I think they compliment each other. In any case I'm pleased with the final result.

I mounted it on the wall of Room 20 at ITP for our midterm presentation. I never thought I'd be drilling something into a wall at school like that.

I didn't use proper screw drywall anchors to mount it because I wasn't going to do that for a quick and temporary mount. Because of that I couldn't get the screws to go in all the way and I couldn't use my screw caps. When I mounted it at home I had to do a better job. I used drywall anchors and mounted it securely to the wall.

After mounting it I had a great deal of difficulty getting the screw caps in place. Most of them didn't want to go into the holes. I got them in with some hammering but it wasn't easy. I'll have a hard time when I move out of this apartment but for now it makes me very happy.

Comments