The History and Vision of the 70's Video Art Movement

During the late 60’s and early 70’s Sony began selling a portable video camera that could be carried and operated by a single person. This new technology offered novel opportunities for ordinary people to record and distribute their own videos. Video camera proponents saw them as a revolutionary tool that could and should be used for the betterment of humankind. This dramatic vision formed on top of the countercultural revolution occurring at the time that saw itself as working to raise human consciousness by fighting against long-held cultural norms of behavior and advocating for the civil rights and antiwar movements. Although the drive to explore video camera technology was to a large extent fueled by the broader countercultural movement, the use and exploration of video cameras also contributed back to the counterculture by being a real tool for change. In time portable video cameras did in fact have a profound influence on the evolution of our culture and that influence only grew as the technology become more ubiquitous and the infrastructure to support its distribution developed into what we know today as the Internet. To a large extent the vision of the early video camera advocates has been realized today but not all of the technology’s effects on our society have been positive. Therefore, there is more work to be done if video recording by ordinary people is to continue to be a positive contribution to the further development of our culture.

The Counterculture of the 60’s and early 70’s was an anti-establishment movement that saw the arrival of the Hippies and other alternative lifestyles. The Counterculture supported the Civil Rights Movement, Feminism, freedom of speech, and other progressive social causes. The movement was adamantly opposed to the Vietnam War and the draft. Challenging authority was popular, as was experimenting with drugs, sexuality, and cultural norms.

By Ric Manning - Own work, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7029083

The origins of the Counterculture movement are often attributed to a generation’s rejection of capitalism, the military, and consumer culture. However, In Fred Turner’s book From Counterculture to Cyberculture, Turner argues that its origins also lie within the military-industrial research culture itself. [1] During WWII there were many new collaborations between scientists, engineers, and administrators, and these collaborations led to many important technological advances that were critical to the war effort. Turner cites the vision of Vannevar Bush and his seminal work As We May Think (1945). [2] During the war Bush was head of the US Office of Scientific Research and Development and coordinated the activities of a wide range of people to build weapons of war, including the Manhattan Project. Before the war many of those scientists and engineers were often in competition with each other for new discoveries or would be willing to collaborate but were unable to find out about other people’s discoveries and learn from their ideas. Bush saw what they could accomplish when the previous barriers were removed and feared that after the war those barriers would return. Instead, Bush wanted to see the new collaborations continue, but for the betterment of humankind and not for war. In As We May Think, Bush addresses this by proposing a giant repository of human knowledge called the “Memex” that would link together documents and information contributed by scientists, engineers, and other knowledgeable people. [2] The functionality of the system he describes sounds in many ways like the Internet as we know it today. That system could not be built with the technology of the time but Bush identifies a very real opportunity for human advancement through the needs and motivation behind the “Memex.” The Counterculture also saw this opportunity and was inspired to look for tangible ways satisfy that need.

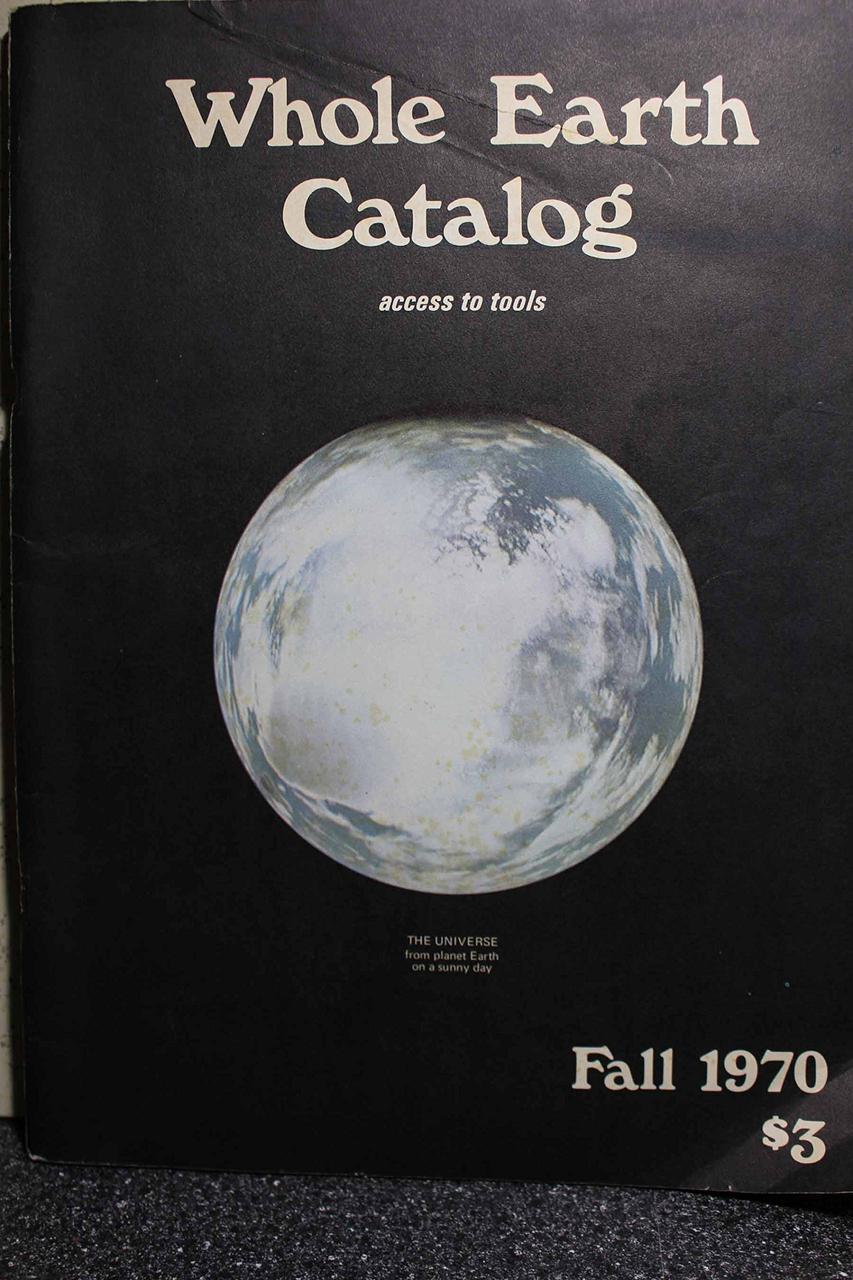

The Counterculture’s motivation to create new mechanisms for collaboration inspired Stewart Brand to start the Whole Earth Catalog in 1968, providing “access to tools.” [3, 4] The Catalog was a regularly printed publication that served as an information sharing and networking platform until 1972, and sporadically thereafter that until 1998. The catalog was held in high regard in its time and was even described by Steve Jobs as the “bible of his generation.” What was unique about this publication is that instead of information being distributed solely from a central authority, information was being shared in something that could be described as a peer-to-peer network. The Catalog was valued by people immersed in the Counterculture movement because it gave them an opportunity to circumvent traditional channels telling them what was relevant or important.

Content found in the Whole Earth Catalog spanned a wide gamut of subjects ranging from arts and crafts to fabricating lodging to new technologies. The common theme was providing readers with the latest products to help them engage the world in a new way and become more creative and capable people. A large section of the Catalog was devoted to products that were available for sale along with price and seller contact information. These products were curated by Catalog editors and were chosen for their usefulness as tools, uniqueness, relevance to self-learners, and availability by mail order. There was also a section for reader submissions where people could share things they’ve learned or new ideas they had about how to approach things. [3, 4]

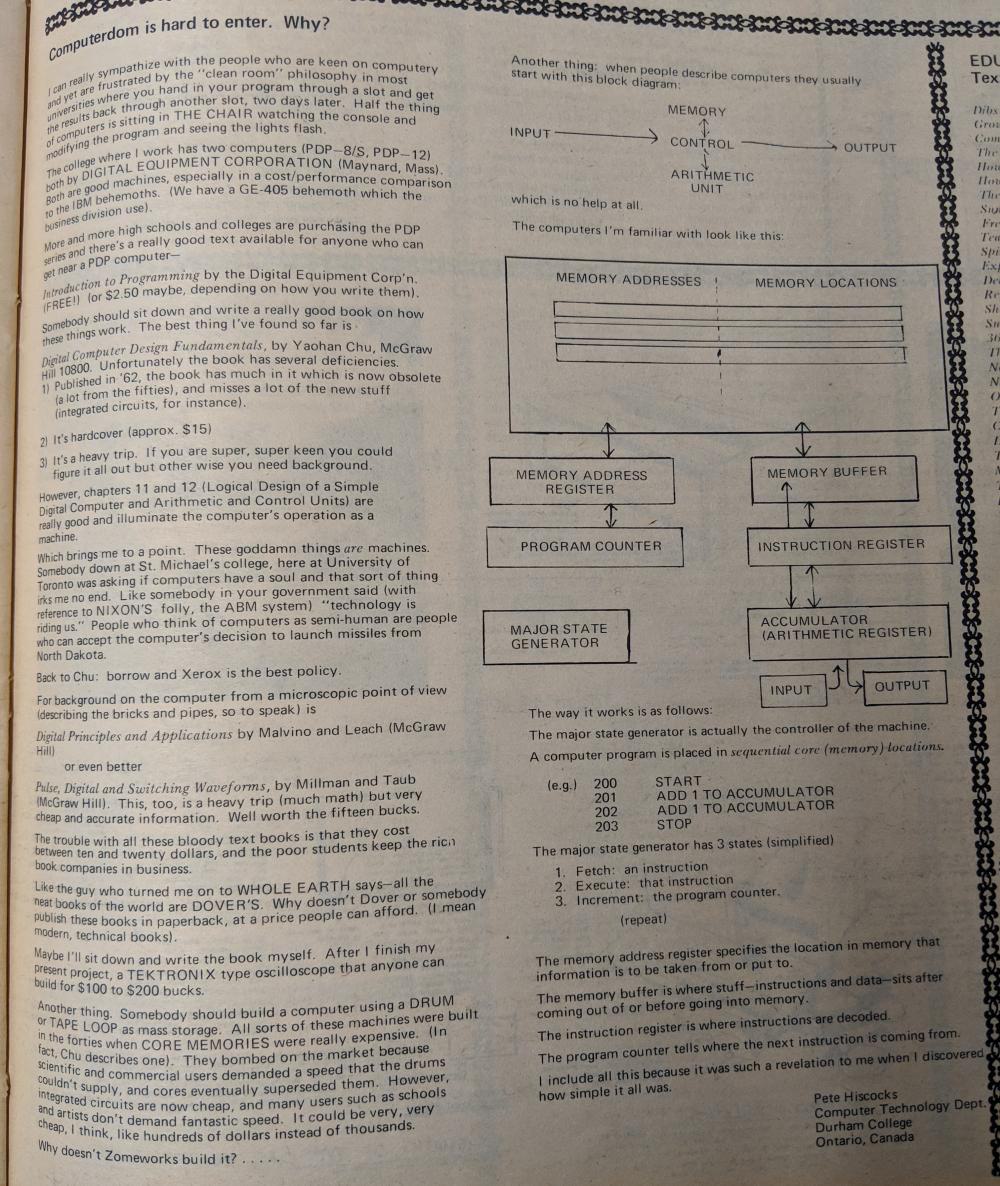

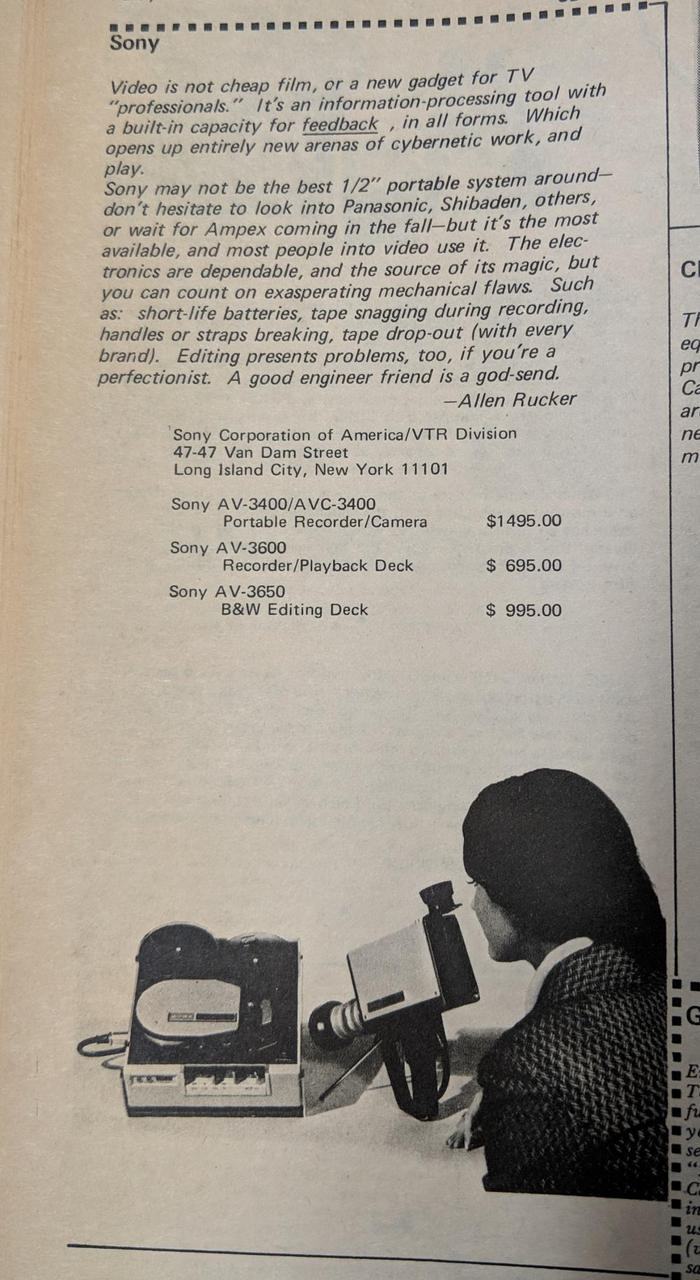

Included in the Whole Earth Catalog submissions are references to computers and new technologies. For example, one article discusses the capabilities of a computer system designed to make “full length cartoon motion pictures” and animate user supplied artwork. Another explains the inner workings of computer architecture in a way that is accessible to novices. Both are evidence of the curiosity people had about technology and the technological experimentation that was taking place at the time. The Catalog also advertised new technological products, some of which related to film or video. The most relevant of these kinds of products is the Sony Portable Recorder/Camera, also known as the Sony Portapak, available for $1,495. [3, 4]

The Sony Portapak camera, introduced in the late 60’s, was a battery-powered video recording system that could be carried and operated by one person. This contrasted markedly with the large camera equipment employed by traditional television broadcasting. The hand-held Sony camera had a built-in microphone and a monitor eyepiece to allow the operator to see what was being recorded in real-time. The camera was connected to a tape deck with a cable. The Portapak contained a battery to power the system that could be recharged in 5-8 hours and provided up to 60 minutes of operation. There was also a jack for an auxiliary microphone. Inside the Portapak were two tape reels: the supply and the takeup. During operation the half-inch magnetic tape moved from the supply to the takeup reels after passing through the recording heads. The deck could also playback previously recorded footage or show what was being recorded in real-time. Critically, the tape could be erased and re-recorded, unlike traditional film technology that could only record images a single time. This made operation of the camera much cheaper and encouraged ad-hoc experimentation. Videographers could record things without a script or a definitive plan as would be required with the more expensive film technology. This, combined with the camera’s portability, is what made the system so innovative. The camera opened up new opportunities and inspired visions for how it would change our culture. [5]

Proponents of video cameras made bold statements about how humanity would be changed as a result of the new technology. In the Meta-Manual of Michael Shamberg’s Guerrilla Television, Shamberg writes that “any time there is a radical shift in the dominant communications medium of a culture, there’s going to be a radical shift in that culture,” and later adds “the dominant technology of a culture determines its character.” [5] A generation of children were growing up with television sets in almost every home, with some children spending more time with the television than their own parents. Clearly television was becoming the dominant communications medium. The structure of the television broadcast medium saw all content and information coming from a central source, which Shamberg associates with totalitarian societies. He contrasts that with democratic societies that “respect two-way information channels which have many sources.” He issues a dire warning that “unless we redesign our television structure our own capacity to survive as a species may be diminished.” [5]

Michael Shamberg was a member of a video collective called Raindance, and the collective published a journal called Radical Software that advocated for the exploration of video technology. In the first issue the editors warn that “Unless we design and implement alternate information structures which transcend and reconfigure the existing ones, other alternate systems and life styles will be no more than products of the existing process.” [6] The editors saw power in the age of television as something that comes not from land or capital but from “access to information and the means to disseminate it.” Broadcast television aggregates all of the power to a small number of television networks. Radical Software wanted that power to be seized by the Counterculture so that its ideals might thrive.

In Expanded Cinema, author Gene Youngblood reminds us that “seeing has been equated with understanding” and emphasizes the relationship between what we see and our formulation of what reality is. [7] Video, being primarily a visual medium, becomes critical to our interpretation of reality and therefore should not be controlled by a small number of television broadcasting stations.

The vision of video technology’s proponents was for video camera technology to enable ordinary citizens to create and distribute their own video content instead of consuming what was provided by broadcast television. This was the tremendous opportunity created by the low-cost and portable Sony Portapaks and their erasable and re-recordable tape. People could use the Sony video cameras to record anything they decided to record and then share those tapes with other people. This contrasted markedly with broadcast television. “Because the technology limits the number of available channels,” Shamberg writes, content must be homogenized and have wide appeal to be justified in being included in the programming. Instead Shamberg wants there to be a “diversity of options.” He wants readers to see video as a “general-purpose technology” that can be used in a variety of ways beyond its use as broadcast television, and that “a generalized video system requires the decentralization of the means of production as well as those of distribution.” [5] Portable video technologies like the Sony Portapak can enable that decentralized production and distribution because individuals can produce their own content on tapes that can then be distributed to others. If this vision of decentralized production and distribution were to become a reality it would create the “two-way information channels” respected by democratic societies. It is precisely because of this vision that Shamberg emphasizes that using media as tools and not just for political propaganda can bring about “enormous social change.” [5]

Shamberg proposes an “electronic or video Whole Earth Catalog.” He is clear that he doesn’t want this video version of the Catalog to have video producers recording the content and information of others; instead he wants the people who would be recorded by these producers to create their own content about themselves. He compares this with the print version of the Whole Earth Catalog, stating that it is:

...people using a familiar medium (writing) to transfer information from their own experience, not about that of others. Thus the video analogue will require people living with portable video cameras, feeding themselves back to themselves to develop a sense of video self and video grammar, and meanwhile building up a personal and public access video data bank. [5]

This video version of the Whole Earth Catalog wasn’t actualized in Shamberg’s time but clearly this is exactly what we are seeing with video sharing on social media platforms today.

Inspired by this collective vision of the potential of video camera technology, individuals and collectives began experimenting with the Sony video cameras in an earnest effort to change the world. These experiments included video activism, documentaries, news reporting, and interviews. Experimentation also included experiments with the mechanics and electronics of video cameras and televisions themselves, exploring what could be created with this new tool.

The pioneer of video art is the Korean-American artist Nam June Paik. In 1965 he purchased the first Sony Portapak delivered to the United States. While stuck in a traffic jam, Paik used the new camera to film Pope Paul VI’s visit to New York City. Paik screened the footage for friends in a cafe later that afternoon. He went on to explore the medium extensively throughout his career. His most notable work is Buddha Watching TV (1974), consisting of a Buddha statue facing a small television displaying a live camera feed of the statue itself. Paik first created this to fill an empty gallery space in a show, and he continued to iterate on this theme later in his career in other works such as TV Buddha (1976). Another notable work is TV Bra for Living Sculpture (1969), performed in collaboration with cellist Charlotte Moorman. Paik also experimented with using the television as a sculptural object, as demonstrated in his later works Li Tai Po, (1987) and Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii (1995). [8]

Paik also created art that experimented extensively with the electrical components of televisions and cameras. With the assistance of electrical engineer Shuya Abe, Paik built tools like the Wobbulator to alter the normal electronic operations of these devices to create unique special effects. These kinds of experiments point to a relationship with the technology that is radically different from that of passive consumption of broadcast television. Instead of televisions and cameras being regarded as magical or sacred devices, Paik is seizing control of them in a fundamental way. [8]

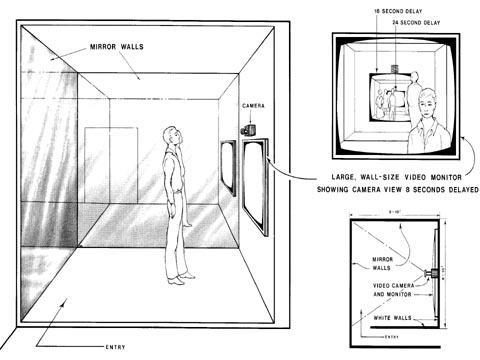

A notable early work that also challenges the expected operation of video equipment is Present Continuous Past (1974) by Dan Graham. In this piece Graham put a camera and television on a wall in a room with mirrors on all four sides. Looking into any mirror the observer sees their reflection, their reflection of their reflection, and so on. The television is displaying what the camera recorded but with an 8 second delay. Since the camera is also recording the television’s reflection, viewers can see what happened in the room 16 seconds ago, 24 seconds ago, 32 seconds ago, continuing ad infinitum. [8] Configuring a camera and television to display what was recorded with an 8 second delay is possible with two tape decks. The first tape deck records images from the camera onto magnetic tape, and instead of the tape being consumed by the second takeup reel, the tape exits the deck and travels several feet to a second tape deck. The second tape deck reads the magnetic tape, displaying the images to the television. The length of the delay then becomes a function of the distance between the two decks. [5] This technique was employed by other video artists at the time with similar results.

http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/works/present-continuous-pasts/

Another early pioneer of video art is Joan Jonas, beginning with Organic Honey's Visual Telepathy (1972). In this performance piece Jonas used a Sony Portapak camera to record herself and project the image onto the stage. A later work, Vertical Roll (1972), is a video of herself performing on stage on a television with the vertical alignment intentionally miscalibrated, causing the image to rhythmically scroll downwards. The vertical roll disrupts the physical space displayed on the screen while again challenging the expected operation of video equipment and exploring the technology as a new artistic medium. [8]

One of the earliest video collectives was Videofreex, a group with 10 core members that experimented with Sony Portapak cameras as a tool for documentaries, interviews, news reporting, and activism. The Videofreex were also devoted to video evangelism, teaching people to “talk back to their television sets” [9] by producing their own video content and sharing it with others. In addition, the group also pioneered interactive call-in television shows and started the first pirate television station.

The Videofreex originated in 1969 through a chance meeting of Parry Teasdale and David Cort at Woodstock. Together with Cort’s girlfriend Mary Curtis Ratcliff, the trio formed a group dedicated to exploring the potential of portable video technology. At the same time, an executive at the broadcasting station CBS named Don West wanted to create a new television program to reach out to alienated young people. He connected with the Videofreex and hired them to produce content for the show. While on a trip to Chicago to interview Abbie Hoffman during the trial of the Chicago Eight, the Videofreex had an opportunity to interview Black Panther leader Fred Hampton. That recording became the last interview of Hampton before he was murdered by police five and a half weeks later. [10]

The Hampton interview is significant in the chronology of the Videofreex because it led to a breakdown of their collaboration with CBS. The broadcasting station wanted to air the Videofreex’s Hampton footage along with their own footage of the funeral. The group saw that as manipulative television and as a corruption of their work, so they refused to cooperate. [11] This led to a mutiny where the Videofreex separated from CBS and kept the video equipment. At that time they snuck back into the CBS offices to repossess the video footage they had created using an empty guitar case; this incursion itself was also videotaped and footage of the event is a part of the documentary Here Come The Videofreex (2016). [11] The group felt that they had a political obligation to people like Abbie Hoffman to not let CBS keep possession of the tapes.

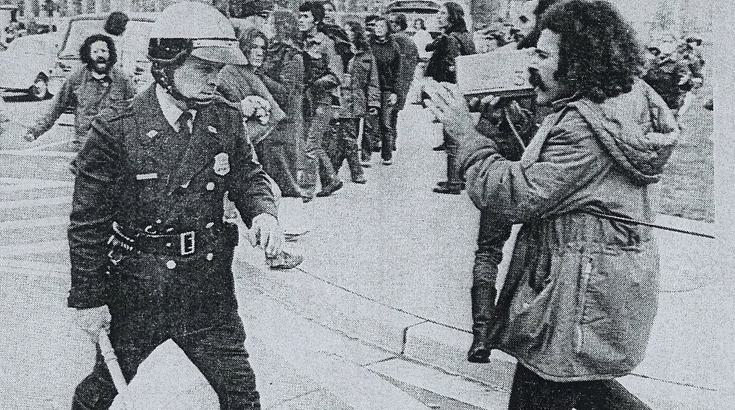

Now independent of CBS, the Videofreex continued to experiment with video technology while becoming “the TV network of the alternate culture.” [9] The collective worked out of a SoHo loft on Prince street while becoming more proficient in the use of video technology and sharing their knowledge with others. Videofreex member Skip Blumberg said that it was a time of “experimentation with the new medium...making tv shows,” and not “cheap films.” [9] The Videofreex contributed to the May Day Collective, a group of video camera collectives that captured video footage of the 1971 May Day Protests. Activists protesting the Vietnam war blocked traffic in Washington D.C. resulting in over twelve thousand arrests, which was the largest mass arrest in U.S. history. The footage from the event was startling and the Videofreex felt an urgent need for the public to see it so people would see what was really going on. They “recognized the power of it, but …couldn’t realize it. Because what good was it if people didn’t see it?” [11]

Prompted by the urging of Abbie Hoffman, the Videofreex began prioritizing the distribution challenges of video technology so that their work could reach a wider audience. Hoffman was able to provide them with a transmitter but they were unable to use it in a large city like New York. At the time New York City was becoming an expensive place for the group to operate so they applied for a grant from the NY State Council of the Arts while making plans to leave New York City. They received the grant and in 1971 moved to a small town in upstate New York called Lanesville. There they began producing and broadcasting the first pirate television station, Lanesville TV, while also collaborating with and educating the broader video community. “We were Johnny Appleseed,” Blumberg says, “spreading the knowledge of making video.” [9]

The audience size of Lanesville TV was small but that was not an issue for the Videofreex. Skip Blumberg explains that “It was really not an audience making thing, it was a chance to play with live television, it was a broadcast channel and we would reach at most 100 people, but we didn’t mind... having 15 people at a screening, because for us it was about quality and the doing of it, and not having anybody tell you what to do.” [9] The Videofreex used Lanesville as their primary audience while also distributing tapes through the mail using other avenues like Radical Software. The group continued broadcasting the Lanesville TV station until 1977 and remained a collective until 1978. [10]

The Videofreex along with other collectives and individuals in the 70’s video art community had high expectations for what could be accomplished with the new technology and altruistic goals for what it should be used for. With a historical perspective one can examine to what extent they accomplished their goals and where they needed to wait for the technology to continue to evolve.

In the 70’s the video art community faced two broad challenges: production and distribution. The accessibility and portability of the Sony Portapak video camera was clearly a game-changer by putting production tools in the hands of individuals. Unfortunately the Portapak’s price tag of $1,495, more than $9,700 in 2018 dollars, made it accessible only to individuals who had the means to obtain one. Although the video collectives like Videofreex and Raindance did rent out their equipment to address this issue and improve accessibility, the extent of the accessibility was nowhere near where it is today. Now the 70’s vision of Sony Portapaks no longer seems radical because everyone has a smart phone in their pocket and can effortlessly produce video recordings. Today, “kindergarten kids can make video art.” [9] The past video art community did accomplish much regarding the production challenges but it has effectively become a non-issue today.

The other challenge faced by the 70’s video art community is how to distribute the videos they were producing. Here they had significant difficulties reaching beyond small audiences. Tapes could be copied and shared through the mail and were advertised through periodicals like Radical Software. While in New York City the Videofreex hosted Friday night screenings where videos produced by the collective or other video artists would be shown to audiences of 25 to 100 people. In Lanesville the Videofreex reached about 100 people with their pirate television broadcast. In addition, the shows they produced were being shown on some cable television channels. At the time the video community hoped that cable television would grow and solve many of their distribution problems. The technology behind broadcasting television signals through the air was limited to a small number of channels. Cable television could transmit many more channels and the video community wished for the expanded bandwidth be made available for them to distribute their work. Public access cable television did emerge in the 70’s and continues to persist to this day but it does not compare to the distribution power of the Internet and social media. With the Internet, individuals can effortlessly distribute their videos to the public without having to negotiate with a cable company as an intermediary. In aggregate the public is “building up [the] personal and public access video data bank” as described by Michael Shamberg in his book Guerrilla Television. [5]

Although the production and distribution challenges faced by the 70’s video art community have been solved with the advent of the Internet, new problems and challenges have emerged. Today people producing videos face an audience problem because of an overwhelming amount of content available for the public to watch. Skip Blumberg explains that for content producers, “the problem is you can... get access to a wider audience, but to get them to know about it is impossible. Most people don’t get the wider audience. You have to depend on going viral. [There is] no formula for that.” [9] Eliminating the production and distribution challenges has resulted in a sea of video content with producers now faced with the challenge of how to build an audience for their work. Currently there is no straightforward approach for addressing this problem.

Another problem is with the video screens themselves, through which we consume all video content. “Video technology is a polluting medium,” says Skip Blumberg. “All the wires, all the chemicals to make screens, the rare earth metals” are polluting our environment, both from mining the materials to electronic waste disposal. Additionally, the “position of the screen in our lives” is a problem because “we are totally reliant on the screen. We spend the majority of our time dealing with the screen, so it is … taking over our lives.” [9] Screens have become a primary interface through which we interact with or learn about the world. Skip Blumberg goes on to explain that in the 70’s:

...our struggle was the military industrial complex and the over-powerful input of corporations and the super-rich. We still have the same problem now, but we also have the problem of the screen itself. So we are attached to the screen. We work for the screen which doesn’t have any values at all. Corporations have greedy values. Profit making vs public good. The screen is the system and has even greater demands. [9]

This is not something that was anticipated by the video community in the 70’s. Although screen addiction is not yet a diagnosable psychological ailment, it is clear that video screens are playing a more significant role in our lives and one that is sometimes toxic and detrimental to the lives of individuals.

With screens playing such an important role in our lives, one can question how it contributes to or detracts from our connection and compassion for humankind as a whole. Violence viewed through a screen can make us more connected to another’s suffering or make us more distant from it. For example, the Rodney King beating video from 1991 amplified the suffering of a man placed under arrest by the police and ignited a national debate about the practices of law enforcement and the use of force. The distribution of the video gave visibility to a systemic problem that was previously neglected. [12]

The Rodney King beating video contrasts markedly with video shared by the US military during the first Iraq war. The military used video as a tool to build public support for the Gulf war, perhaps after understanding how video turned public opinion against them during the Vietnam war. Videos from “smart bombs” were shown on the nightly news, flying themselves to their intended targets and avoiding any collateral damage. Night vision videos of the Air Force attacking Baghdad showed stealth bombers in the air and anti-aircraft fire from the ground. In many ways the videos seemed like something from a video game and not real people being killed. This video footage created distance between the viewers and the consequences of the violence that was taking place. [12]

A notable video from the second Gulf war, released by the organization Wikileaks, documents Apache helicopter pilots killing people incorrectly identified as combatants. The video, recorded from one of the helicopters, shows the little regard the soldiers had for the civilians that were being killed. Using the helicopter’s weapons systems through a screen made the violence again seem like something from a video game and not real people being killed. At the same time, the public’s response to the video after its release was one of increased compassion for the people being killed and anger towards the military. In this example, the video both created and removed compassion for the suffering created. [13]

Video technology has complicated our relationship to violence, both increasing and decreasing our compassion for the suffering of those viewed through the screen. In the 70’s the video community thought that video technology could increase compassion for others and attempted to do so by distributing their May Day Protest footage and Fred Hampton interview. The fact that video could also decrease compassion for others was not something that was anticipated. This, combined with our addiction to our screens and the pollution caused by the hardware, show that video technology’s effect on humanity has not always been positive.

The arrival of portable video cameras has had a profound effect on the development of our culture. Early adopters of the technology saw it as a revolutionary tool and wanted to see it contribute to the betterment of humankind. The 70’s video community was able to shape the impact the new technology had through their explorations of the medium and through their efforts as video evangelists. The community’s vision of what video technology could achieve was vast and could only be partly achieved in their day. It was only after the arrival of the Internet and the ubiquity of smartphones that the full vision was actualized. Although this has clearly been a positive result for our culture, the success of this movement also created unanticipated problems that need to be addressed if video technology is to continue to contribute to the further development of humankind.

Bibliography

[1] Turner, Fred. From Counterculture to Cyberculture. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2006.

[2] Bush, Vannevar. “As We May Think.” The Atlantic, July 1945.

[3] Portola Institute. The Last whole earth catalog; access to tools. Menlo Park: Portola Institute, 1971

[4] Portola Institute. Supplement to the Last whole earth catalog. Menlo Park: Portola Institute, 1968-1971

[5] Shamberg, Michael. Guerrilla Television., Second edition. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1971.

[6] Phyllis, Beryl & Gershuny, Korot, eds. Radical Software. New York: Raindance Corporation, 1970-1974.

[7] Youngblood, Gene. Expanded Cinema. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1970.

[8] Hall, Doug & Fifer, Sally Jo, eds., Illuminating Video. New York: Aperture Foundation, 1990.

[9] Blumberg, Skip. Interview by James Schmitz. Personal Interview. New York City, November 9, 2018

[10] Ross, David A. Videofreex - The Art of Guerrilla Television. New Paltz: Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art, 2015.

[11] Here Come the Videofreex. Directed by Jon Nealon & Jenny Raskin. 2015. USA. Moldy Tapes, Film.

[12] Bender, Gretchen & Druckrey, Timothy, eds., Culture on the Brink. Seattle: Bay Press, 1994.

[13] McGreal, Chris. “Wikileaks reveals video showing US air crew shooting down Iraqi civilians.” The Guardian. April 2010.

[14] Teasdale,Parry D. “Lanesville TV.” Experimental Television Center. 1993.

Comments